Corey Spence

BATS Theatre is, in many ways, the mother of the Wellington theatre community. It welcomes emerging artists with open arms and provides a place of nurture to help those artists grow and eventually fly from the nest. BATS Theatre is embedded in Wellington’s theatre community, and so many of us have ties to our winged friend, one way or another. Like all the wonderful and valiant mothers in our world, those they nurture always strive to return the favour, by giving back to the person (or people in this case) who helped them along their way.

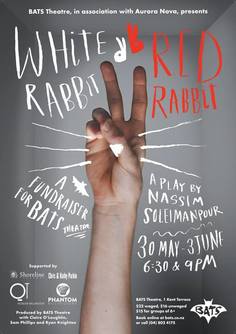

Enter White Rabbit Red Rabbit: a fundraiser for BATS Theatre and an early birthday celebration for the time it has stood and helped artists create their work. BATS Theatre runs on a co-op, meaning both the theatre and artists take an equal risk in producing a show, with both taking a cut at the end and most returning to the artists to help inspire and allow for future work. Therein lies the necessity of fundraising. For BATS, it’s a method to help keep them flying, to help keep them facilitating the minds and imaginings of the emerging artists, and to help broaden the future of the theatre community.

Nassim Soleimanpour, an Iran playwright, is the mind behind White Rabbit Red Rabbit. His work is a cultural and theatrical phenomenon, first debuting in 2011 but now performed more than one thousand times across the globe in a multitude of languages. Soleimanpour was unable to leave his native country, and so wrote a play that could travel the world in his place. Famously quoted saying “Why can’t an actor just get up and start,” White Rabbit Red Rabbit is a play one can only discover in the moment, a play one can only experience by seeing it.

I met with producers Claire O’Loughlin and Samuel Phillips, and BATS Programme Manager Heather O’Carroll, to gain some more insight into the production. I wanted to explore some of the challenges involved with producing White Rabbit Red Rabbit, to discuss the importance of community-driven theatre in Wellington, and to discover what drew each interviewee to this production.

Much of theatre can be or is an experiment, but White Rabbit Red Rabbit separates itself from the herd. While experimentation in theatre typically surrounds pushing form or practice, Phillips explains this show “almost combines what you would receive from a social experiment and a theatre experiment”. Truly, it’s unlike any production I’ve ever heard of before: the audience, the performers, everyone involved enters a complete unknown. The show dictates the performers view the script and perform it on the spot, creating a spontaneous experience for all, and placing a massive risk on everyone involved. The ‘experiment’ factor for White Rabbit Red Rabbit comes from the resulting performance – it’s nigh-impossible for one performer to replicate what another has done previously or will do in the future. Created in the moment and for the moment, each production is a ‘controlled unknown’; each a personal and new experience for performer and audience member.

Often when producing a written work, the production reserves tickets for the author, in case they show up to see the production. “Now, normally, this doesn’t happen.” O’Loughlin begins. “It’s not like Arthur Miller will rise from the grave and go to your production of The Crucible. But for White Rabbit Red Rabbit, we reserve a seat for Nassim Soleimanpour, for his spirit, to watch. So he can travel the globe in that way.” There lies a connection between the playwright, his text, and New Zealand – we are separated from much of the world geographically, so perhaps this helps attract our artists to the production. In a more political context, there's much debate on the treatment of and quota for asylum seekers, and the promises of extreme vetting, deportation laws, immigration suspensions, and of course, the border wall proposed (and in same cases, enacted) by the Trump Administration have created fear, strife, and hardship globally. While White Rabbit Red Rabbit is not overtly political, O'Loughlin clarifies, one can definitely relate these wider issues to us and the context in which Soleimanpour found himself in when writing the play.

O’Carroll reveals that several of the performers have been “saving themselves for this show.” The performers for this season of White Rabbit Red Rabbit in alphabetical rather than performance order include Keegan Carr Fransch, Ricky Dey, Moana Ete, Daniel Gamboa Salazar, Kali Kopae, Salesi Le’ota, Karin McCracken, James Nokise, Jo Randerson, and Mick Rose.

White Rabbit Red Rabbit has the capacity to celebrate BATS Theatre and its years and years of patronage and lineage. “The performers are from the Wellington theatre community, those who have invested their time into BATS as it’s evolved over the years” O’Carroll mentions. In addition to the performers being active members of the Wellington theatre community, several community projects and companies have helped make this production a reality. Their supporters include The Parkin Foundation, Shoreline partners, Phantom Billstickers, QT Museum Hotel, and Rabbit Ranch.

White Rabbit Red Rabbit requires the introduction of the performer each night, and so the creative team is using the show as a platform for the awesome organisations involved to talk briefly about their work before each performance begins each night. The organisations presenting introductions are Changemakers Refugee Forum, Pomegranate Kitchen, Big Live Arts Group (BLAG), Double The Quota campaign, and Molly Kennedy from Multicultural Learning and Support Services and the Asia Pacific Refugee Rights Network. This allows audiences to engage with the supporters and presenters in addition to the actors and the play and invites the organisations involved to engage with the work and be part of the experience.

White Rabbit Red Rabbit helps create a cyclical venture: organisations and the theatre community invest into the show, which helps maintain BATS Theatre, which then feeds back into the theatre community and provides exposure for the organisations. Everything going into the production goes back into the community, “embod[ing] the values and virtues of BATS Theatre,” O’Carroll says.

Phillips has seen a production of White Rabbit Red Rabbit previously, and cites an unparalleled intrigue as the lure guiding him to this production; “it’s engaging in a way I don’t see often”. He, as well as his colleagues, spoke about figuring out why audiences would want to engage with the show in the first place was part of the challenge, to provide an incentive to wider audiences. Though, I think there’s definitely some form of appeal from the outset. Mysterious and provocative, it’s easy to see why artists, in particular, might be drawn to such a production.

O’Carroll describes her pull to the production as celebrating and connecting the community: “I have a 20-year history with BATS Theatre”. On 1 April 2019, BATS turns thirty, which is a massive milestone, and everyone at BATS, past and present, recognises that twenty-eight years, let alone thirty, wouldn't have been possible without the love and support of the community. One of her favourite things about the show is the celebration of “Wellington theatre lineage”; some of the performers involved performed at BATS when it first opened, and another has yet to perform there! There's a magical entwining of the past, present, and future of the Wellington theatre community with White Rabbit Red Rabbit, and BATS Theatre provides the perfect stage for such a melding.

O’Loughlin’s attraction to the production stems is a combination of both work and community, and much like Phillips and O’Carroll, she too wanted to stretch BATS out to the wider Wellington community. As a fan of experimental theatre evidenced by her work with Binge Culture Collective, she wants “to make audiences think about they’re seeing, capture them and draw attention to wider issues”. White Rabbit Red Rabbit seems a perfect fit; it brings in organisations from the community to support and present, which makes more people aware of BATS, those organisations, and anyone involved. Oh, and she really, really wanted to work with Sam Phillips.

While not overtly political itself, White Rabbit Red Rabbit provides a platform to delve into wider issues, to get out of our own heads for an hour, and simultaneously celebrate the beauty of our theatre community and our supporters. With no director, a different actor each night, and a script no one’s read, anything really could happen. From what I’ve heard, White Rabbit Red Rabbit feels like an exceptional choice of a BATS fundraiser: it’s experimental, it pays homage to the community, it provides a platform for artists and organisations, and it’s relevant for the now. I’ve been asked to plead with anyone reading this article not to research the play any further – shrouded in enigma, this might pose tempting, but resist and watch it live at the theatre you love, with the actors you love, with the organisations that helped make this season a reality.

White Rabbit Red Rabbit begins its BATS Theatre season on Tuesday 30 May and runs until Saturday 3 June. There are two shows each night, with one at 6:30pm and the other at 9:00pm. For ticketing information or to book tickets, please visit the BATS Theatre website, and visit the event’s Facebook page if you’re eager to catch a particular performer. In conjunction with their season, the creative team is also hosting a raffle. Included in the Great White Rabbit Red Rabbit Raffle: an overnight stay in an Executive King Suite at QT Museum Wellington; a $75 voucher at rooftop tapas bar Basque; a $50 voucher at The Botanist in Lyall Bay; a double pass to any BATS Theatre show; and two bottles of Ranch Rabbit wine. You can purchase these raffle tickets also through the BATS website.