Jack McGee

So before I start being quite critical of Nailed It! – A Builder Play, I think it’s important to stand back and approach this with some perspective. This isn’t broadway. The theatre is filled with laughter, for pretty much the duration of the show. The audience is happy. They get to see their friends and whanau have a great time on stage, and good for them! My plus one and I were the only grumpy-looking sour-pusses in the room. Judged purely on the satisfaction of its audience, Nailed It! whole-heartedly succeeds at what it aims to do.

That being said, this is a public show, released as part of NZ Fringe. It appears to have received sponsorship from BCITO (a building apprenticeship provider), Toi Poneke, and of all places, Night ’n Day. It’s contributing to a wider artistic conversation, and deserves to be treated as such.

In my critical opinion, Nailed It! – A Builder Play is a catastrophically un-funny, somewhat homophobic, and deeply regressive comedy. It takes me back to the experience of being in high school and doing impressions of the school drop-outs with my nerdy upper-middle-class friends. I cringed watching it for the same reason I cringe thinking back on those memories. Just because you put on a silly voice when you say the offensive, crude, or sexist thing, doesn’t mean you’re criticising or commenting on it. It just means you’re trying to find a way to say it without anyone being able to call you out.

The play follows the complications that erupt on a building site after the death of a 106-year-old builder named Pete-o (Brandon Entwistle) brings on harsher safety regulations in the form of queer-coded safety inspector, Donald (Sam Lewis). This coincides with the arrival of the site's first woman builder, apprentice Dylan (Aimee Dredge), with the two posing as a double threat to its deeply entrenched, grossly masculine culture.

Initially, the builders of this show resemble my high-school friends’ impersonations. That same uncomfortable cocktail of dehumanising stereotypes and toxic-masculinity-role-play. The site-lead Crusty (Tom Hayward) is mostly spared, being portrayed as kinder and less overtly sexist than his employees. Bubbles (Shauwn Keil) is nasty and menacing, proving as Dylan’s main obstacle into assimilating into the team. He’s buddied up with the comically crude and exaggeratedly dimwitted Brick (Brock Oliver), whose idea of comedy is holding a hammer in front of his crotch and pretending it’s his penis. They’re complimented by the “sell-out” Spanko (Logan Tubman Wallis) and sex offender Wanko (Alex Fox). Wanko’s creepiness is played for laughs, with Crusty warning Dylan about him and implying that he, of course, masturbates on site.

A frequent issue in storytelling, is how can we make sure that we humanise a controversial community (builders) while being able to comment on and critique aspects of their culture (oppressive masculinity, defiance of safety regulations). It’s a hard tightrope act, the balance between laughing at a group of hard-working people from our liberal high horse, and celebrating the things that keep their industry dangerous and exclusionary to women and queer people. This show manages to achieve the worst of both worlds.

As described above, the characters are thinly drawn piss-takes. Each of the men is played with an exaggerated Kiwi drawl, going as far as to literally mention the ghost chips advertisement by name. Brick and Bubbles are pie-crazed fiends, and when it comes time for smoko, we are greeted with an extended comedic set-piece of them trying to steal Dylan’s pie. This scene doubles as the first piece of overt product placement I’ve ever seen in a theatre show, with her revealing that the pie is from Night ’n Day. This, of course, gives it a magic sheen that turns builders into cartoon magpies as they attempt to pinch it. Congrats Night ’n Day, you got your money's worth.

Moving over to the culture side of things, the play ultimately rules in favour of the hammer-penis. Dylan’s arc is one of assimilation. Early in the play, she specifies that she’s fine with all the hyper-masculine tomfoolery. She just wants to be one of the boys. Her routine and sexist humiliation by the men is portrayed as a slight overstep of “normal” hazing rituals. Even Crusty, who's portrayed as the nice guy, is incredibly handsy with her, tossing his arm over her shoulder and touching her an uncomfortable amount. In the first act, I thought it was setting up for some form of commentary or statement in the third. Instead, Dylan ultimately defends the men to Donald, the safety inspector. This moment, played as heroic by the play, is heartbreaking to watch. This woman stands up for her belligerent abusers in the hope that they’ll treat her like one of their own. The thesis of the play is clear: there should be more women in construction, as long as they behave like men.

Then there’s Donald the safety inspector. I mentioned earlier that he was queer-coded, meaning that he falls into the trope of the effeminate, overly friendly, city boy who just doesn’t get it. Donald serves as the villain of the piece through attempting to shut the site down. His utterly rational calls for PPE are met with derision and laughter. Late in the play, his “villain backstory” is revealed. Donald and Crusty used to build together, and it’s heavily implied that Donald was in love with him. Their friendship was shattered when Crusty got his first job on a building site and adopted their sense of humour, causing Donald to abandon building and become a safety inspector instead, seemingly out of revenge. As if this isn’t insulting enough, Donald has his pants pulled down in the climax of the play, and the audience laughs at his (admittedly fantastic) floral boxer shorts. He then apparently doesn’t know how to pull his pants back up, and is forced to waddle offstage.

While everything with Donald and Dylan is offensive whichever way you look at it, it only stands out as much as it does because the show completely fails to be funny. I would love to be carried away by Nailed it! – A Builder Play, but it’s a dire hour. The actors have little sense of comedic timing, and the script pushes in favour of crude puns (bang is said very frequently) and contrived comedic set-pieces (A PPE fashion show, the “builderlympics”) instead of any wit or actual jokes. Which in some ways, is a bit of a betrayal of builders, and other blue-collar workers in Aotearoa. For all the sexist and questionable humour in these communities, these guys tend to be good at getting a laugh out of each other. If a real dyed-in-the-wool builder found himself doing a hammer-as-a-penis bit, he’d find a good punchline.

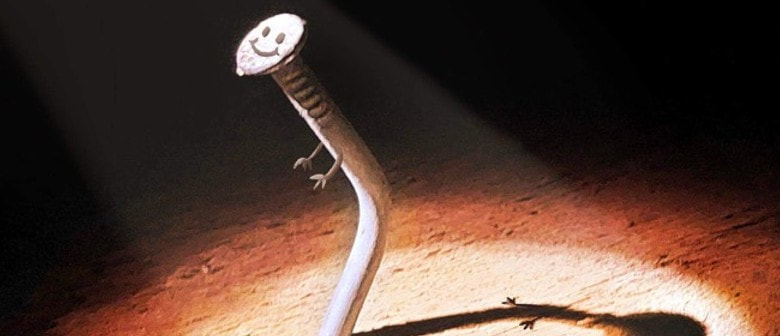

I will mention that the play does attempt to comment somewhat on the culture, through a subplot where Crusty secretly writes musical theatre songs but is scared to share them with the other builders. The play takes another half-step towards saying something at the very end, with the builders agreeing to somewhat change their ways in order to stay open, by wearing hard-hats. Dylan nails in a protruding nail that has sentimental value to Crusty, symbolically changing the culture of the site and making it safer for all.

But the gesture is token. Everything around it speaks at a much higher volume. Nailed It! – A Builder Play may be a riot for the friends and whānau of those involved, but I can’t help but worry about what it’s saying to them. While comedy should be allowed to be silly, I think it’s worth considering what, or who, we’re getting our audiences to laugh at.