Alia Marshall

The show opens with a jovial song and dance introducing us to the world of the play, and eventually the novel. The flight boxes are filled with copies of Frame’s novel that - to my delight - are distributed amongst the audience during this sequence. Toby (Arlo Gibson) invites us to not only interact with our books by creating a soundscape, but to consider the weight of the words inside them, and the story which this performance responds to.

Frame’s debut novel deals with the story of the Withers whanau in small town Aotearoa following a tragedy that impacts each of them in different ways. As mentioned in the director's note, this is not an adaptation of the novel, but rather a response to it. An exploration of what’s considered the first great Aotearoa novel that gives us a brief glimpse into Frame’s rich, lyrical world. I must admit, I hadn’t read the novel before attending the show, but I don’t think I needed to (that’s not to say I didn’t run to a bookstore the second I had a chance to buy a copy).

The direction, by Malia Johnston, is flawless. Shows with so much physicality, scenography, and room for interpretation can be difficult to pull off, but the cohesion of the ensemble and Johnston’s vision bring it together with such harmony. Decisions made onstage are intentional and precise, taking us on a journey through so many highs and lows with precision and care.

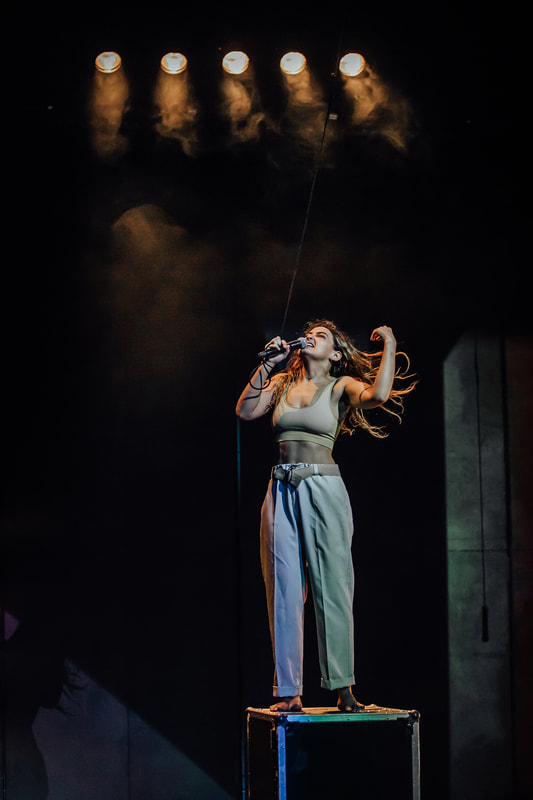

Daphne (Comfrey Sanders) has one of my favourite moments, staunchly holding the audience in the palm of her hand as she commands the lights around her while reciting one of the few monologues in the show (if you’ve seen the trailer, you know the scene I mean). Chicks (Katrina George) is not heard from until the very end, ever present but wordless until the final few moments. Part of me wishes we heard more from her character, but part of me loves the idea of being the forgotten sibling of the family. Arlo Gibson delivers a visceral performance as Toby, his dead eyed stare is something I won’t forget soon, and the relationship between him and his father drew more than a few tears out of me. But what was the most incredible thing to watch was how each performer enjoyed every second onstage, to see an artist enjoying their craft with such playfulness and joy truly is a gift.

Owls Do Cry is a reminder of what theatre can and should be. Not only is it a visual masterpiece, incorporating some of the most stunning AV I’ve seen in a long time, but it’s also a masterpiece in storytelling, in remembering our literary whakapapa. To see Janet Frame’s words and mind brought to life in such a visceral, touching, and dynamic way is an incredible introduction to the author, so I promise you don’t need to have read the book! I implore you to see this show while you can, surrender yourself to the poetry, and allow it to linger in your thoughts like it did mine.

Owls Do Cry is on at Circa One until the 13th of November.