Corey Spence

Punk Rock focuses on the stresses of being a teenager, centring around several high school students readying to sit their Advanced-Level GCE examinations. New-girl Lily Cahill (Molly Weaver) meets model student William Carlisle (Shauwn Keil), who ensures Lily’s transition to her new school is smooth. And their interactions are cliquish, often failed attempts to coexist when they really don’t want to, like with lovebirds Cissy Franks (Alexandra Taylor) and her boyfriend Bennett Francis (Mila Fati), who is barely tolerated; Hot-for-teacher over-achiever Ashleigh Low (Tanya Gleason); shy lesbian Nicola Chatman (Maia Diamond); and brainiac Chadwick Meade (Kasey Benge). As the story unfolds, lovebird Bennett shows a cruel streak, severely and continuously bullying Chadwick. Each character is enticing and realistic, and as their stresses culminate, one shows us how far they’re willing to go when pushed, ignored, and frightened.

While we experience enough of the characters’ everyday and mundanities to see them as real and empathise with their stresses and worries, it’s this focus on the play’s thematic concerns that afford Punk Rock its impact. Phillips’ direction shapes the character journeys and continuously subverts audience expectations. There’s not much surprise in the plot, so Phillips focuses on how events play out rather than what is going to happen next. He toys expertly with pacing as we learn more about the characters; we gloss over the scholastic fears of the students when their daily discussions begin, and sit for extended periods when Bennet’s abuse hits full swing. The result leads us down one path, and even if we figure out what twists await us, Phillips subverts these expectation with how the twists happen. The play sets us up to expect certain students to crack and rumble, only for us to discover it isn’t so black and white. Nothing turns out exactly I how anticipated. I begin to consider even further that it’s not the characters who need nor want the focus in this story, but what is happening to them, why it is happening, and what any bystanders should do. And it’s this thinking that leaves a profound impact on the audience: What would I do and how would I cope?

Together, the cast is an active ensemble, and the play’s best moments are when the whole group of students are interacting or involved in the action. Fati portrays Bennett as an overwhelming juggernaut; from his dominating posture to patronising tone whenever he ‘jokes around’ with Tanya or William or the others, you picture a bully you once knew or one you wished you’d stood up to. Keil plays William with incredible skill and subtlety, showing us both William the manic head boy, all scattered-brained movement and endless questioning, and the self-doubt underneath his drive: there’s nuances of uncertainty and fear woven throughout Keil’s performance. It’s saddening to watch William crumble under his stress, but an all too real reminder that someone’s outside appearance doesn’t always reflect how they feel on the inside. I feel an intense sorrow for Ashleigh Low’s Tanya, who is one of the few characters who starts with the confident to stand up to Bennett when he first picks on Chadwick. Her arc is disheartening, watching a strong, driven young woman succumb to Bennett’s totalitarian reign over their friend group, and watching her falling to cope during the play’s climax is absolutely gut-wrenching. Physically, her poise, relaxed yet confident posture reduces to jagged movements and hurried scurries.

Kasey Benge’s Chadwick is surprising and endearing, showing us the resolve and perseverance of the human spirit. As he spends much of the play downtrodden, Benge slinks onto the stage after everyone else, recognisably the outsider. Nervous and almost meager, he’s a font of knowledge that is the target of Bennett incessant and horrific bullying. However, Benge finds moments of revolt in Chadwick’s weakness: with every knock Bennett deals to Chadwick, we see Benge hold on to each of those moments, watching the courage build physically in his body through his glaring gaze, his curled fists, his weathering posture. We sit waiting for him to snap back, hoping it’ll be the end of Bennet’s tyranny.

Punk Rock’s music maps the play along its narrative journey. Upbeat starting rap song floods the airwaves, establishes a calm before the storm as the students are studying in their library. Gradually, the music shifts and descends into angstier tunes as the play progresses and the performers grow more tense -- the Arctics Monkeys receive a reference, here. Similarly, the lighting design (courtesy of Glen Ashworth) builds on the stage’s atmosphere. Much of the show exists under washes, warmer with softer yellows and oranges at the beginning, transfiguring into colder blues and violets as the students learn of the death of their History teacher, as the fears and stresses of passing their GCEs to acquire university entrance build, and as their friendships seem to collapse more and more. The light bounces off the set, intricately built from wooden pallets, covered with a thin layer of white plastic. It suggests a school corridor setting to the audience, coupled with the familiar scuffing of sneakers, but looks unfinished as the plastic covers only the surface area of the pallet floor and not its sides. Since the students are studying at a private school, as denoted by their swish uniforms, I’m confused and sometimes distracted at the decision.

Punk Rock isn’t an easy story to watch; it is deliberately uncomfortable. However, this is part of where its power comes from. With such power is a responsibility to show the severity of mental illness among teenagers, and it’s a responsibility Phillips and his team take aboard with both care and conviction. Simultaneously earnest, delicate, and confronting, Punk Rock is both important and powerful.

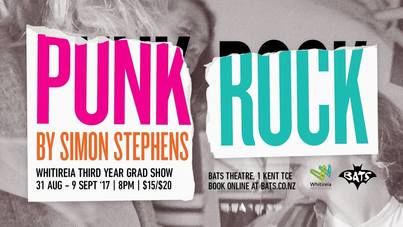

Punk Rock is currently showing at BATS Theatre until Saturday 9 September. For ticketing information, please visit the BATS Theatre website.

NB: The show’s programme does not specifically credit a set or sound designer.